Pickpocket and Life’s Absurdity

There’s a lot of Crime and Punishment in Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket. The DNA is evident: a fragile man who thinks himself above the dictates of morality; a viscous inner mind that twists recursively, guiltily; an impoverished woman whose devotion may pierce this petty criminal’s heart; and an inspector who may be playing mind games, or maybe not be paying much attention at all.

But Bresson takes Dostoevsky’s mold and fills it with his own spirit. Bresson’s centers his film on a poor young man named Michel (Martin LaSalle), and Michel’s crime is far less brutal than Raskolnikov’s. Instead of a strong willed man straining against society’s ideals, Michel only weakly aims at such superman philosophizing. In his mouth, the ideas are derivative and unconvincing. Instead, his crimes are driven by necessities of poverty as he tries to care for himself and his ailing mother. Bresson forces us into the simplicity of his life. Michel may not be Bresson’s titular prisoner in A Man Escaped, but his home is hardly more inspiring. Ironically, his own lock is missing, stripped from the doorframe. It’s a brilliant and encompassing character detail.

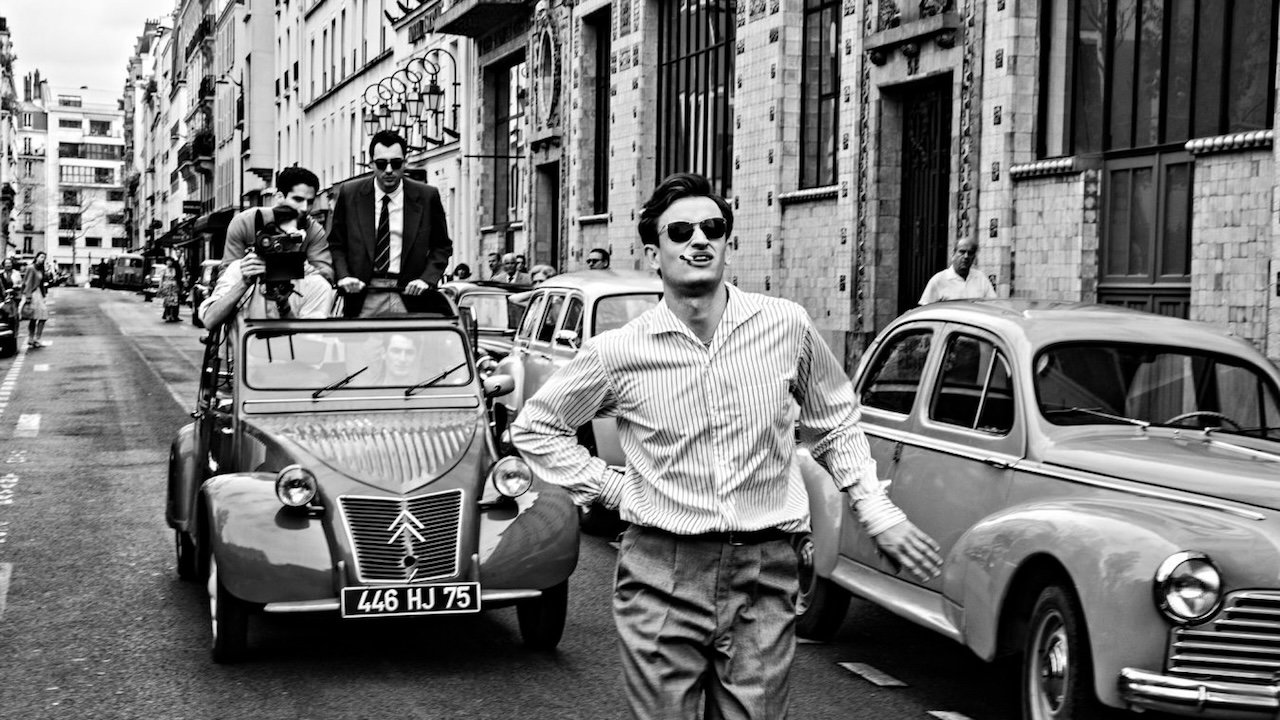

LaSalle’s thief somnambulates around Parisian streets with soulful, almost immovable eyes. His appearance makes it clear that he’s a man who’s looking for nothing so much as a place in this world. “The world is upside down,” he claims. Pickpocket is less interested in making bold philosophical declarations than in embodying sociological empathy. When Michel cries out to his friend Jeanne (Marika Green), “Do you think we’ll be judged? By what laws? It’s absurd!” it’s not from a Zarathustran mountaintop, but from the valleys of economic hardship. His cry is less aimed at God than at man.

Of course God is not far, even as he remains quiet. If Pickpocket echoes A Man Escaped, it bears more than a resemblance to Diary of a Country Priest. The austere apartment is where Michel journals out his days, and his thoughts pervade the narration like a ghost. So, too, are Bresson’s filmmaking techniques on display. There’s a tenuous intimacy in the actual thefts: Michel leans into his mark slowly, their eyes briefly meeting as his fingers slip into the pockets of their clothing. We also see foreshadows of other films to come. When Michel finally confronts Jeanne about his identity as a thief, he unleashes a ferocity that would later be honed even sharper by James Caan in Michael Mann’s Thief.

Pickpocket is about the absurdity of poverty. The absurdity that our actions could be punished; the equal absurdity that they could have any merit. Maybe we have agency, maybe we don’t. But either way, why would it actually matter?