The Classic Feel of Punch-Drunk Love

Across the many films of Paul Thomas Anderson’s career, he’s shown a dexterity and playfulness with genre that perhaps no other contemporary American director can boast. Melodramas that morph into biblical epics, sun drenched noirs that descend into postmodern absurdity, refined romances that reveal themselves to be more about maneuvers for power than desire. All of these find neat homes within Anderson’s filmography, and all of them have found adoring audiences.

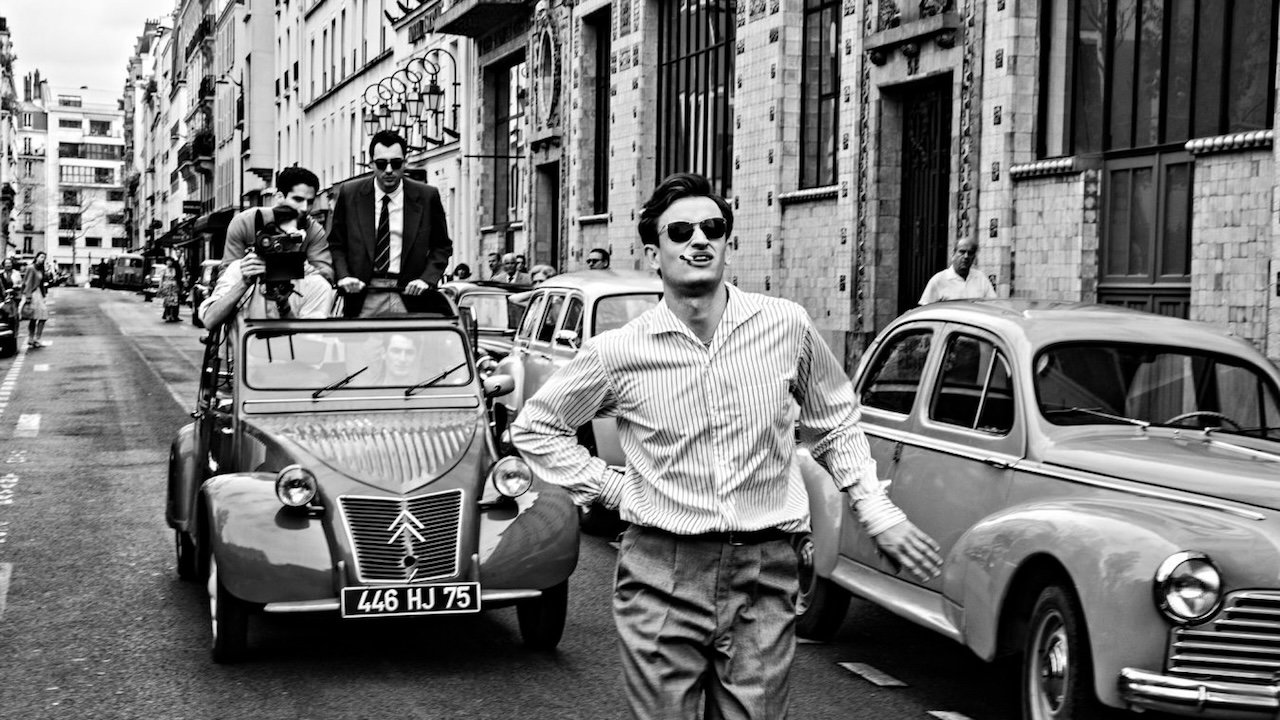

Even twenty years out, Punch-Drunk Love still rings as the most inventive genre work of all of his films. What appears on first glance as an Adam Sandler comedy quickly becomes something altogether more nervous and sad, but as it unwinds, it wholeheartedly embraces a classically romantic sensibility. It is nervous and sad, erratic and volatile; it’s also warm and imbued with longing. The movie is a screwball, cringe romantic comedy.

Punch-Drunk Love traces the pains, anxieties, and desires of Sandler’s Barry Egan, the owner of a small company that sells colorful plungers among other odd paraphernalia. It’s successful enough, but perhaps not the sort of work that makes for easy friendships or impresses dates. Business stresses are less constricting than his chronic anxiety and the burdening pressures of his many sisters. Barry tries to maintain his composure, but there are times his anger gets the best of him—shattering the windows at one sister’s house or unleashing a tirade of threats on whoever happens to be in his way.

It’s both a smart and subversive use of Sandler. Anyone who’s watched any of his comedies knows the sheer level of havoc he’s liable to rain down at any moment. But Barry is far more introspective and self-conscious than other Sandler creations, resulting in a character tortured by raging emotions with little healthy exercise for them. He’s also a bit of a schemer, taking cheap coupons from pudding to earn airline miles for fractions of the cost. At another point, finds an abandoned harmonium and, as a creative outlet, goes to work delicately repairing and tuning it. Even this side of Uncut Gems, it remains Sandler’s most articulate performance.

The most welcome disruption to Barry’s life is Lena (Emily Watson), a friend of Barry’s sister Elizabeth. The idea of romance, of opening up one’s self to another, initially terrifies Barry. He makes every excuse he can to avoid being set up with Lena, but his reticence can’t outlast Lena’s interest.

The film’s true essence comes into focus as their relationship grows. Punch-Drunk Love is a deeply romantic film; even so, it never abandons the nervous energy. Instead, both aspects are ratcheted up until the movie becomes a dizzy rush of outsized emotions. Punch-Drunk Love is romantic comedy in the vein of Cukor, Hawks, and McCarey, a pulsing warmth beating within an antic plot.

Anderson leans into the romance even when the scene doesn’t. His frame is humanistic. Messy. Like Barry, the cinematography is emotional, but there are hints of transcendence. Anderson is also frequently referential, having fun creating homages to classic scenes or shots. There’s even a camera movement that inverts Taxi Driver’s pan in the hallway that indicates PTA’s compassion for Barry.

Punch-Drunk Love has a sly playfulness to it. It appears particularly of its time, but its heart is unabashedly old school. Anderson uses homage to call us back to romances—doomed or otherwise—of the past. This again provokes a tension. Are Barry and Lena in their version of The Graduate or The Awful Truth? Where will this road lead?

Once again, the movie wears its heart on its sleeve, and the bright colors of the title card have it their way. No matter what anxieties crush us in life, there’s a power to love that can call us outside of ourselves. It pulls us toward others, crashes us into the lives of others with all our anger and longing and wonder and fear. And even there, in the mess of it all, we find something of substance.