The Angles and Shapes of Challengers

Luca Guadagnino’s Challengers is a film of angles and perspectives, a film about searching for the best footing and always being off balance. And this is magically as true for the audience as its characters. There is rarely a moment of pause, a chance to catch one’s breath, a rest. The match is starting up again and we’re always thrown right into the action.

A rectangle: the white lines making right angles against the blue and green surface to create the tennis court. The stark, painted abyss of the rectangles emphasizes the court as an exposed, existential proving ground. Then there’s the net, of course—another rectangle rising up from the surface and enforcing a separation. Enforcing again the isolation of each player.

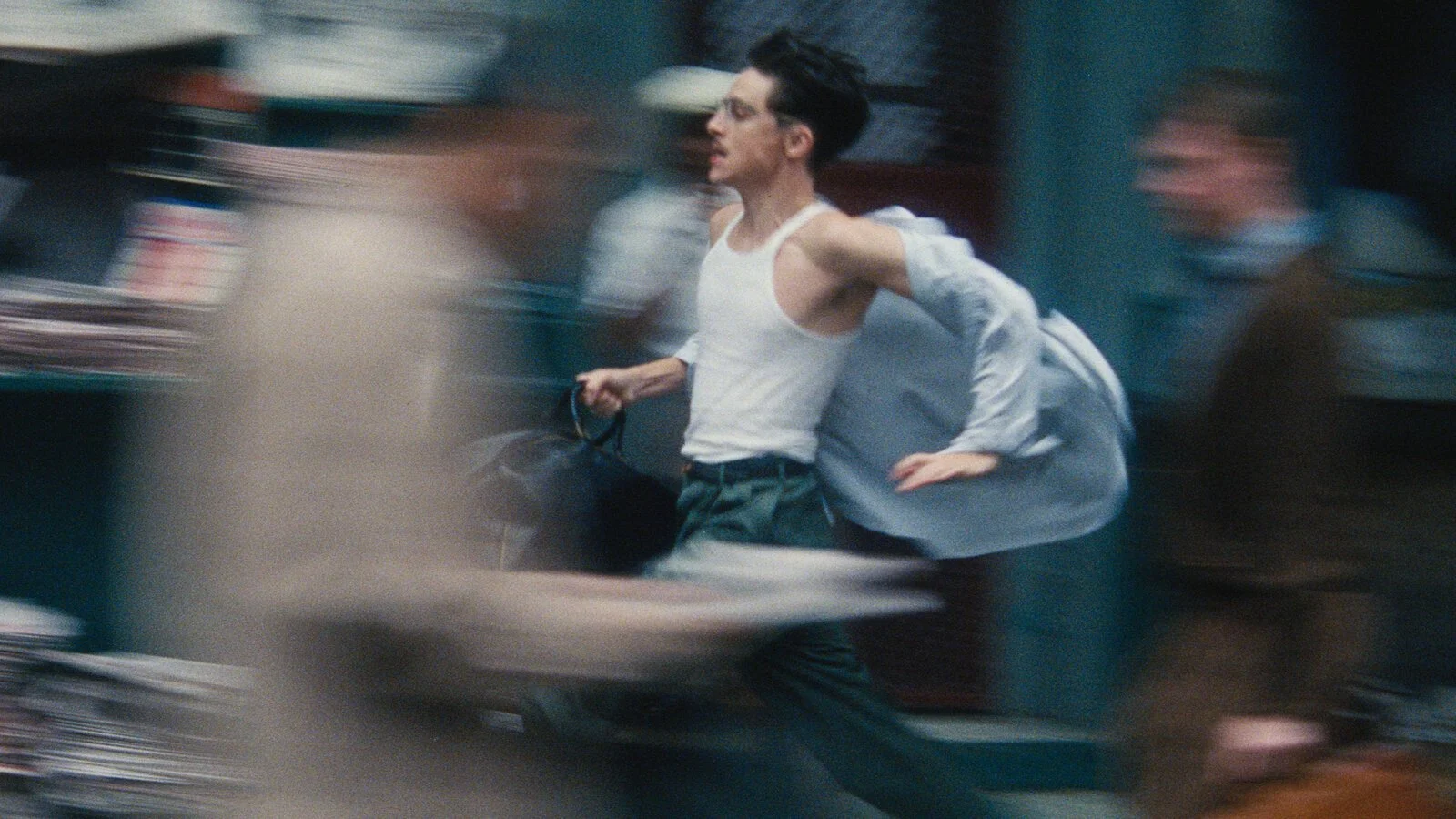

When play begins, the action on the court reveals and heightens the character of the player. Styles, tics, aggression, and impatience are all unveiled, but they also shape the ensuing match in a tricky dynamic. For Pat (Josh O’Connor) everything is an angle—where can he press and catch his opponent off guard, how can he find leverage. And when a volley doesn’t go his way, his anger immediately expends itself. Art (Mike Faist), on the other hand, feigns insouciance and composure. It’s a game—one he’s great at, mind you, but still a game.

Though they were once best friends and teammates, playing on the same side of the court, Art and Pat are now isolated by the forces of time, desire, frustrated hopes, and competition. Not to mention that net.

A triangle: enough with symmetry, because the gravitational pull of Challengers lies with a third point: Zendaya’s Tashi. In the past, Tashi was a rising tennis star before a tragic injury, and she was also the object of fixation for both Pat and Art. A college relationship with Pat broke off in the same instant she shattered her knee. Her current marriage to Art seems fruitful, but weariness is beginning to erode their contentment, just like it’s beginning to erode Art’s career.

When Art and Pat enter the same competition, everything—grudges, desires, confessions, dreams—gets served in a volatile back and forth. Guadagnino matches the intense nature of the narrative through the filmmaking, keeping the adrenaline rushing. Working from Justin Kuritzkes’ script, Guadagnino cuts between the present day match and scenes from the past, thus intrinsically weaving the stakes of the match with the import of everything these characters have experienced together.

The tennis match cinematography begins still and staid, but only for a moment. It gradually ratchets up until the techniques become truly wild. But the style persists beyond the match. In every conversation there are sly angles and editing: we are always watching someone, always from someone else’s point of view. The framing separates the characters in moments of tension and unites them in desire—or in threat. The editing emphasizes the movement of emotion and power, constantly shifting angles between the three of them, never allowing a balance. The verbal volleys and sharp returns are even more electric than those on the court.

The unruly filmmaking is both matched and tethered by the acute performances. Faist, O’Connor, and Zendaya all throw themselves into the competition and land some vicious strikes. Their characters express themselves well beyond the dialogue—Pat is explosive and belligerent, unabashed about trying to get what he wants (be it Tashi or a breakfast sandwich); Art is a little more pent up, but his fear and pain shows on his face. Faist’s strongest moment comes as the climax approaches, as Art prostrates himself in front of Tashi. The walls come tumbling down in a moment which is equally intimate and ominous. Zendaya accomplishes the toughest role in Tashi, at once responding to Art and Pat’s advances and acting as instigator propelling them both forward.

Expressive performances and frenetic cinematography are accompanied by Trent Reznor’s feverish score and a narrative that gives no hints about where it will end up. Look, this film is an all-around hell of a good time, okay? The conceit of Challengers—and its success—is captured in its deception. Because despite one character claiming that there’s “nobody on the other side of the net,” it never really was an isolated abyss. Challengers is not about the separation of the net, but the ways in which the net can be leapt over. As Tashi declares, it’s not an existential proving ground: “It’s a relationship.”