La Chimera Buries us in the Past

It is simplistic to the point of stupidity to say, but many people lived in the past. To us they are little beyond rumors of people: ghosts and scattered bones and the nameless (or infrequently named) actors of history and the just about always nameless victims of that same history, attended by fragments of coin or cloth or tattered book or jewelry or another mundane object of life. They are not lives—not to us—not lives truly lived. Merely dying echoes of a world that, by necessity, must have preceded our own but bears little existential meaning to it. The truth is the past must bear existential meaning on the present. But we so instantly and so constantly lose ourselves in the now. What can the dead possibly mean to the living?

It is common to the point of meaningless to say, but many people live in the past. We say it thinly, with a condescension that falls somewhere on a spectrum between sad and pointed. And we fling it in enough directions that its purpose dulls: to one who wants to rekindle a lost spark or one who can’t accept cultural shifts or one who isn’t ready for their kid to grow up quite yet or one whose grief runs deep enough that we can’t touch the bottom.

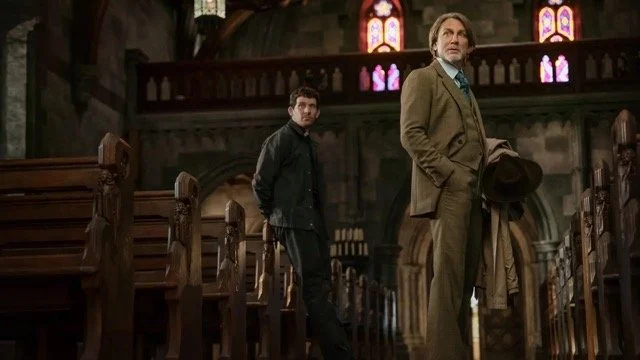

Arthur (Josh O’Connor) is fixated on those who lived in the past and the remnants they leave behind. You could call him an archaeologist if you’re feeling kind—graverobber is a bit more apt, or tombarolo if you prefer to add finesse. We first meet Arthur dozing on a train, fresh from jail and quite worse for wear. We don’t know what got him in jail, but we learn that the benevolence of the unseen Spartaco ensured his release. Arthur’s response to this news is less than enthusiastic, and he isn’t overjoyed at reconnecting to the ragtag group of layabouts and vagabonds that comprise his friends. He’s much more invested in visiting Flora (Isabella Rossellini), an elderly woman who welcomes a ceaseless parade of daughters and is cared for by a new servant, Italia (Carol Duarte). One of Flora’s daughters is Arthur’s lover, Beniamina, who has been lost to them both, though Flora swears she’ll return soon.

Arthur will return to raiding tombs, of course, but his cryptic escapades are preceded and punctuated by other odd adventures. He borrows a coat from Flora, begins learning Italian from Italia, day drinks, and partakes in an Epiphany parade. In director Alice Rohrwacher’s imaginative vision, these meanderings are just as vital to Arthur’s life as digging up artifacts. The people around him are doing all they can to pull him into the present, but it’s a near futile effort.

That’s because Arthur isn’t just interested in the echoes of foregone lives; he does indeed live in the past, in a manner truer and cloudier than any meaning we tend to attach to that phrase. When Arthur does finally get ready to uncover an ancient Etruscan tomb, he grabs a limb off a nearby tree and uses it as a divining rod. The oddity breaks the mundanity, though it remains unaddressed other than when a friend refers to his “chimera.” Arthur is a man drawn to these places, lost in time—he is haunted by the past in a way that startles in its realization. Rohrwacher fractures the neorealist sense of the film in these moments, sharply cutting or tilting to invert the image of Arthur. We are visually disoriented; he is temporally so. History is drawing Arthur into itself—possibly in more ways than one.

O’Connor lists around the Italian coast with a stifled physicality that embodies Arthur’s conflict: remain adrift in the past, or stumble his way back to the present? As he feels the allure of both times grow stronger, Rohrwacher folds other corners of the film in toward the center, layering La Chimera with an unanticipated thematic depth. With the wandering Arthur as its muse, La Chimera is about the many ways we forget old things: relationships, civilizations, people. All of our romances, our accomplishments, and our failures will be as drops in the ocean, indistinguishable in time. Still, those very things we forget may one day be rediscovered. Unearthed and unburied under who knows how many layers of dust.

But will that reclamation lead to a reappreciation, or will those artifacts of our lives become objects for exploitation? Just as we’re adept at forgetting, we’re also rather good at exploiting. An object originally buried to attend a soul to the afterlife—how much could that fetch on the market? Sometimes we begin to forget the elderly even while they live, excusing ourselves from the responsibilities of care while laying claim to their possessions. Or who can judge why we carry our lost loves with us, whether for nostalgia or to nurse bitterness or in hopes of a rekindling.

La Chimera is about the dynamics of forgetting, of exploiting, and of being drawn back, led by a thread of memory or of hope or of longing—how do we differentiate?—to another time. Whether that other time is the past of memory and ancient civilizations, or whether it’s the already slipping and uncertain present, only time will tell.